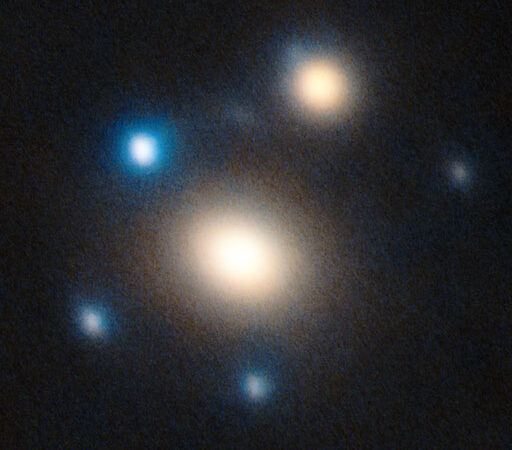

High-resolution image taken with the Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham in Arizona, USA, displaying the two lens galaxies in a warm tone, and the five lensed copies of SN Winny in blue / Credit : SN Winny Research Group

MEASURING THE EXPANSION OF THE UNIVERSE WITH COSMIC FIREWORKS

That the universe is expanding has been known for almost a hundred years now, but how fast? The exact rate of that expansion remains hotly debated, even challenging the standard model of cosmology. An international team of scientists, including researchers from the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille (LAM – OSU Pythéas, CNRS, AMU, CNES), has now imaged and modelled an exceptionally rare supernova that could provide a new, independent way to measure how fast the universe is expanding.

The supernova is a rare superluminous stellar explosion, 10 billion lightyears away, and far brighter than typical supernovae. It is also special in another way: the single supernova appears five times in the night sky, like cosmic fireworks, due to a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

Two foreground galaxies bend the supernova’s light as it travels toward Earth, forcing it to take different paths. Because these paths have slightly different lengths, the light arrives at different times. By measuring the time delays between the multiple copies of the supernova, researchers can determine the universe’s present-day expansion rate, known as the Hubble constant.

“Detecting such an extraordinarily rare event is immensely challenging,” explains Raoul Cañameras, postdoctoral researcher at LAM, who coordinated the team’s efforts to identify gravitational lenses. “A particularly effective approach is to first identify static strong gravitational lenses — alignments of two galaxies along the same line of sight producing multiple images, arcs, or even complete rings — and then wait for a supernova to explode in the more distant, background galaxy.”

To achieve this goal, the team analyzed telescope images of several billion astronomical objects using state-of-the-art deep learning algorithms. “Six years after completing the search, a supernova was finally detected at the position of a gravitational arc listed in our catalog. We nicknamed it SN Winny, inspired by its official designation, SN 2025wny,” adds Raoul Cañameras.

Animation showing the gravitational lensing effect of the pair of foreground galaxies on the host galaxy of SN Winny. The host galaxy is lensed into multiple images, which are distorted and stretched out to form a bluish ring around the lens. The explosion of SN Winny itself and the time-delayed arrival of its multiple lensed copies on Earth are also simulated. Ultimately, the animation fades to a real observation of SN Winny, captured at the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona / Credit : Elias Mamuzic / MPA / TUM / https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MP5gGr-ilBA

High-resolution color image of unique supernova

The analysis of gravitationally lensed supernovae depends strongly on how well one can determine the masses of the galaxies acting as a lens. To measure those masses, the team obtained images with the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona, USA, using its two 8.4-meter diameter mirrors and an adaptive optics system that corrects for atmospheric blurring. The result is the first high-resolution color image of this system published to date.

Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham, Arizona, USA /Credit : Dr Christoph Saulder / MPE

Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham, Arizona, USA /Credit : Dr Christoph Saulder / MPE

The observations reveal the two foreground lens galaxies in the center and five bluish copies of the supernova – reminiscent of a firework exploding. This is quite unusual, since galaxy-scale lens systems normally produce only two or four copies. Using the positions of all five copies, Allan Schweinfurth and Leon Ecker, junior researchers in the team, built the first model of the lens mass distribution.

“Until now, most lensed supernovae were magnified by massive galaxy clusters, whose mass distributions are complex and hard to model,“ says Allan Schweinfurth. “SN Winny, however, is lensed by just two individual galaxies. We find overall smooth and regular light and mass distributions for these galaxies, suggesting that they have not yet collided in the past despite their close apparent proximity. The overall simplicity of the system offers an exciting opportunity to measure the universe’s expansion rate with high accuracy.”

Two methods, two very different results

So far, scientists have mostly relied on two methods to measure the Hubble constant, but these methods yield conflicting results. This puzzle is known as the Hubble tension.

The first is the local method, which measures distances to galaxies one step at a time, much like climbing a ladder, where each step depends on the previous one; hence, it is referred to as the cosmic distance ladder. It uses objects with well-known brightness to estimate distances and then compares those distances with how fast galaxies are moving away. Because this method involves many calibration steps, even small errors can accumulate and affect the final result.

The second method looks much farther back in time. It studies the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, and uses models of the early universe to calculate today’s expansion rate. This approach is highly precise, but it relies heavily on assumptions about how the universe evolved, and these assumptions are still subject to debate.

A new, one-step approach

A third, independent method now enters the picture: using a gravitationally lensed supernova. Sherry Suyu, Associate Professor of Observational Cosmology at Technical University of Munich (TUM) and Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics explains that by measuring the time delays between the multiple copies of the supernova and knowing the mass distribution of the lensing galaxy, scientists can directly calculate the Hubble constant.

“Unlike the cosmic distance ladder, this is a one-step method, with fewer and completely different sources of systematic uncertainties” notes Stefan Taubenberger, first author of the supernova-identification study. Because gravitationally lensed supernovae are so rare, only a handful of such measurements have been attempted to date.

Researchers at LAM, including Raoul Cañameras, Stéphane Basa, and Benjamin Schneider are currently contributing to the follow-up observations essential for completing the analysis of SN Winny. A top priority is to closely track the supernova’s brightness over time to precisely measure the time delays between its multiple images. For this purpose, the team is actively using the robotic telescope COLIBRI, built through a French–Mexican collaboration between AMU, CNES, CNRS, UNAM, and SECIHTI.

Alongside efforts by astronomers worldwide, these observations of SN Winny will deliver critical new data and help advance the resolution of the long-standing Hubble tension.

| Publications |

| Taubenberger et al.: “HOLISMOKES XIX: SN 2025wny at z = 2, the first strongly lensed superluminous supernova”, accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics (A&A), December 2025. Preprint available on the arXiv (arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.21694).

Ecker, Schweinfurth et al: “HOLISMOKES XX. Lens models of binary lens galaxies with five images of Supernova Winny“ – submitted to Astronomy & Astrophysics (A&A) and already available on the arXiv (arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.16620). |

Informations complémentaires :

Press Release of the Technical University of Munich

Contact : Raoul Cañameras, raoul.canameras@lam.fr